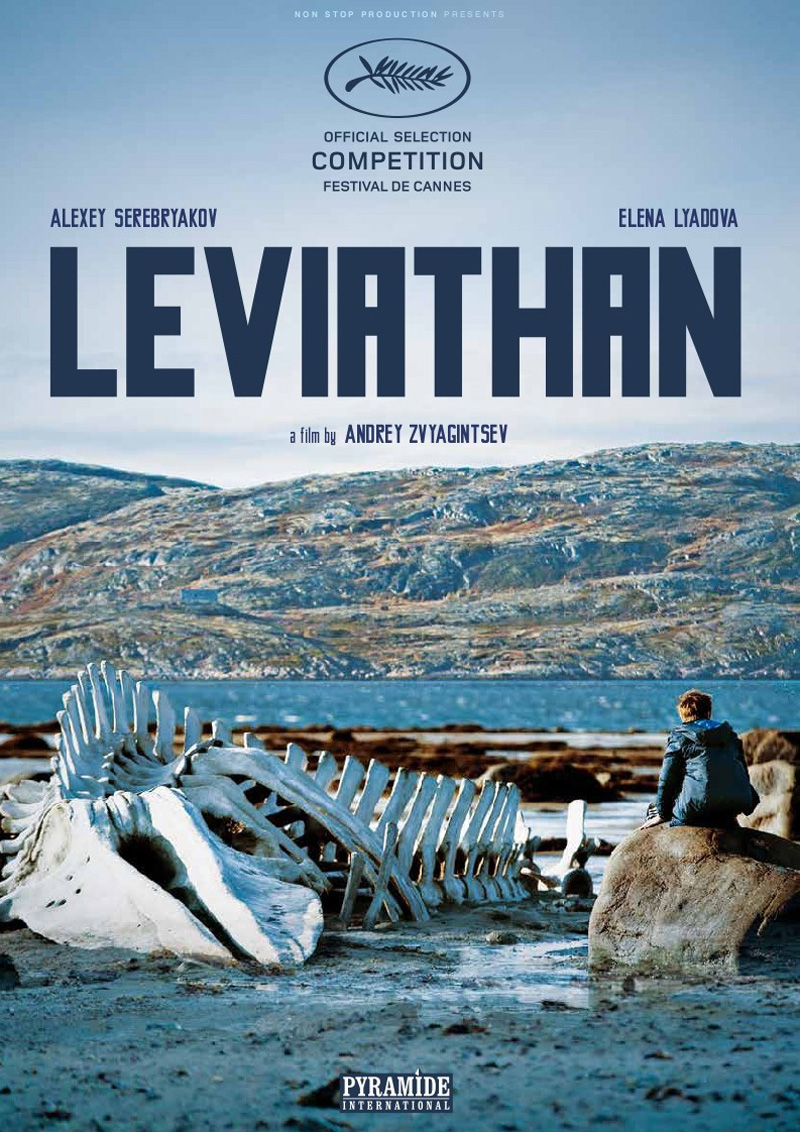

"This is the Generation of the great Leviathan, or rather (to speake more reverently) of that Mortall God, to which we owe under the Immortal God, our peace, and defence." — Thomas Hobbes

Although Andrey Zvyagintsev's highly (and justly) celebrated film

Leviathan obviously connotes Thomas Hobbes' famous treatise, it should perhaps also be linked with one of Nietzsche's most famous lines, specifically when he called the state "the coldest of all cold monsters". 'Leviathan' gives this film not only its title but its whole sense of world; it is a film about structure, about the crushing, irresistible weight of this great, horrible, monstrous, but also

mortal being.

If it can be summed up so simply, the film reflects on the immense, destructive, tragic but also transient force of assembled societal power; a power that seems utterly vast and yet will, in time, crumble like everything else. Churches will become ruins in which teenagers hang out, powerful leaders will become jokes (albeit private ones), whales will wash up and leave only their skeletons on the beaches.

"Canst thou draw out Leviathan with a fishhook?" (Job 41:1)

There is a strong sense of anger but also, overwhelmingly, futility in this film. Non-resistance seems to be the only means of survival for any of these characters (indeed, the Book of Job-speaking priest offers precisely this advice at one point). The protagonists perturb the status quo in the first act but, like a sturdy ship, it rights itself and it is as if that wave had never rolled in. The state's fragility (and here taking 'state' in its broadest sense, including the church, organised crime, and so on), its transience, its mutability is of no comfort to those caught up in its wheels and cogs. It is something that is only even really perceptible on a broader scale of time than that of a human life. It would take the whole 140 years that Job is said to have lived in order to make anything of this mortality. The skeleton on the beach, while deeply symbolic, doesn't suggest any real possibility of resistance. Structural mortality and fatalism come together, without contradiction.

There is far more to this film than I am able to go into here. Despite its bleak themes, it is often very funny and is beautifully shot. Many shots of the decaying ships in the harbour recall the cinema of Tarkovsky so strongly that had they been held for 50 seconds rather than 5 one could have been excused for mistaking parts of

Leviathan for his

Stalker.

In short, the film is about church, state, Russia past and present. The fact that it was sponsored by the Institute Of Modern Russian Culture is interesting in itself. The film treads an extremely fine and precarious line with regard to the current regime. Overt criticism is more or less avoided but the subtext sounds out like a foghorn. The various portraits of Putin hanging about the place, the Orthodox figures of Jesus staring from every mantlepiece (and dashboard), the scene with the portraits of past Russian leaders, the brief glimpse of the words 'Pussy Riot' on a TV screen. Iconographically the film is incredibly rich and it'd take someone far better qualified than me to do any of it justice. It is a remarkably critical film in many ways although clearly one that has elected to mind its historical moment (one character says precisely this in one of the film's most crucial political scenes — a scene that occurs, tellingly, far out in the wilderness, 100km from the small town in which the film is mostly set).

The one other thing I'd like to mention is the law. One of the most striking scenes in the film is found in a court room where the presiding official reads through the judgement so fast that the words become just a blur, a solid block of somehow insignificant signification, a stream of pronouncement without even the slightest hesitation; she barely even pauses to breathe and when she does it seems almost reluctant. It is a barrage, an avalanche, a volley of legalese. The force of the power on display is its total incontestability. Never mind 'getting in a word edgeways,' there is no gap for any objection whatsoever.

It is also quite amazing how

surprised everyone at the police station and courts appear when the hotshot lawyer from Moscow swans in and presents them with legal argument (with the ever so naive belief that this will have some force). It is not only that they do not accept its force, it is that the very notion that they would appears to be the strangest thing in the world. 'What? That is not how things work here,' they seem to be saying. For the most part this is without any particular maliciousness (except for where the principle antagonist is concerned, who is nothing but malevolence, maliciousness and greed). It simply is not the way things are done. It is an alien proposition.

Here we are presented with the

institution of law without its

process. The hollowed out shell, the great fleshless ribcage of the social in a society corrupted, captured by organised crime of one sort or another. Although this is a film on the most ostensive level about law there is precious little legality within it. All legal utterances fall flat against an edifice that has simply rendered them not

unspeakable but

inaudible. (And here perhaps it would be interesting to reflect on the preoccupation of structuralism with speech — 'can the subaltern

speak?' In the case of the main character, a socially privileged male in some respects but utterly incapable of engaging with bureaucratic formality on its own terms, he clearly cannot speak or act in the language of law. And yet when his incomparably more nuanced, cultured lawyer friend speaks for him in perfect, considered, calm but also forceful and pointed sentences he meets an infrastructure simply incapable of

hearing his flawless, metropolitan speech acts.) This is a world in which law has, to all intents and purposes, died; reduced to procedure; reduced to a tool of power, of organisation.

Like so many excellent films, this one has, its excellence notwithstanding, perhaps been a little overhyped. I went into the screening with mildly overinflated expectations. It is not an epic. It is a low budget film with a relatively small cast but, most importantly, big ideas. It is the epitome of what film making should be; however, I certainly didn't find it to be life-changing or anything of the sort. An absolute must watch for anyone interested in political or legal theory, or simply anyone who likes slow moving, beautifully made, slightly dystopian tragedies. Since I tick all of those boxes it is a film that I'll be thinking about for some time to come.