Saturday commenced, for me, with a session on ‘Securing the Atmospheric: On Shifting, Melting, Rising and Geo-Engineered Boundaries,’ chaired by Lukas Pauer of RMIT University.

The first presentation was my old friend Marijn Nieuwenhuis from whom I have heard about half a dozen papers in the last eighteen months, including one earlier in the week. (Once I’ve finished scribbling these posts I have to get on with an essay that I’m due to write for a collection Marijn is putting together—tick-tock, tick-tock…) He spoke about the need for re-engaging elemental concepts, particularly reconnecting with a geopolitics of the air before moving on to the subject of law, particularly the principle from property law: Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos (whoever's is the soil, it is theirs all the way to Heaven and all the way to hell) Paralleling the work of his Warwick colleague Stuart Elden, he talked about “territory’s volumetric cone” and the inherent absurdity in geometric-legal partitions of space that are constantly undone by the forceful dynamics of the pluri-elemental Earth.

I must admit that the conceptual vocabulary of elements leaves me a little cold, although I am gradually warming to it. I find it difficult to extract the classical elements from a sense of purity and essence. If all we encounter is mixture and if air is unthinkable without combustion, oxidation, photosynthesis (to name but a few processes), then what sense does it make to speak of ‘the elements’ in this older sense? I think there is a strong case for looking at how these concepts are embedded in our (European) languages and seeing how this structures our thought. I am sceptical as to whether it makes sense to appropriate them positively as useful concepts in their own right. That said, the use to which Marijn is putting these concepts is an interesting one. I am just left wondering whether elementalism is, on the whole, a plausible avenue for creative thought (but I may be alone in this).

The second paper came from Elizabeth Reed Yarina, ‘Post-Island Futures: Mobility and Territory for Tuvalu’s Sinking Atolls.’ This was certainly the most visually impressive presentation that I’ve seen in a long time, as you might expect from an architecture student at MIT (see this paper of hers for another example).

Finally, Janelle Knox-Hayes presented the work of her collaborator Alyssa Maraj Grahame on ‘Resources of Recovery: Connecting Crisis and Arctic Economic Governance’—a fascinating tour through the recent political economy of Iceland in all its multi-faceted complexity, touching on the incredibly fast recovery from its recent financial and political crises, its heated (if you’ll pardon…) national debates over its geothermal engineering projects and its tendencies towards protectionism against building an export economy.

For the last two sessions of the conference, I joined the section organised by Delf Rothe and David Chandler. The penultimate of these: ‘Environmental Terror: Complex climate change, disasters and resilience.’

First up was Harshavardhan Bhat, another architect who talked about ‘Open hegemony: In anticipation of forgetting architecture.’ This was followed by three German scholars whose papers chimed together, as I heard them, rather well.

Maximilian Mayer in ‘Reducing the complexity of climate change? A comparison of diverging co-productions of planetary order’ spoke about the epistemic technologies—infrastructural and conceptual—that render climatic complexity an actionable object of knowledge. He also mentioned the various political contestations and contradictions surrounding such technologies, particularly around Green politics in Germany; for example, environmental activists resisting the construction of wind turbines for the sake of birds. Delf Rothe in ‘Seeing like a satellite: Of plants, carbon and other securitizing actors’ (great title) spoke about the emergence of these same sorts of technologies from Cold War geopolitics before moving on to discuss planetary emergency, the commercialisation of remote sensing and more besides. Finally, Stefanie Wodrig in ‘Science and emotions as a response to complexity: First evidence from anti-fracking protests in Northern Germany,’ talked about fearful reactions against technologies such as fracking and how these emotions enter into matters of scientific knowledge, the production of expertise and, ultimately, governance.

One crucial thread that was, for me, connecting at least the final three presentations and perhaps all of them was the question of modernisation, something that has been back on the agenda recently. What was in Europe in the 1990s called ecological modernisation theory has been given a brash, slick new makeover for the US market in the form of ecomodernism (on this connection see for example). The principal target of the ecomodernists has been the traditional, allegedly techno-sceptic wing of environmentalism. Against this, the ecomods advise ramping up technological innovation, lassoing capitalism via intelligent state regulation and getting out of the ecological and demographical crises by producing enough wealth that family sizes dwindle and production is concentrated onto industrially intensified portions of the earth. More technology, more capitalism—less environmentalism. Regardless of the pitfalls of this thinking, an echo of this resonated in these papers, even if negatively: the question of modernisation, its varieties and its alternatives.

The simplistic critique often levelled at Greens that lumps anyone who doubts the power of technology to liberate humanity from any- and everything into the same category as anarcho-primitivists is silly. But it is not always without some evidential basis. Very well, so wind turbines will harm birds—but then where, what, when, how? There is no technology without downsides—there must be decision, a cutting off, a cutting out.

I cannot resist quoting Alfred North Whitehead at this point:

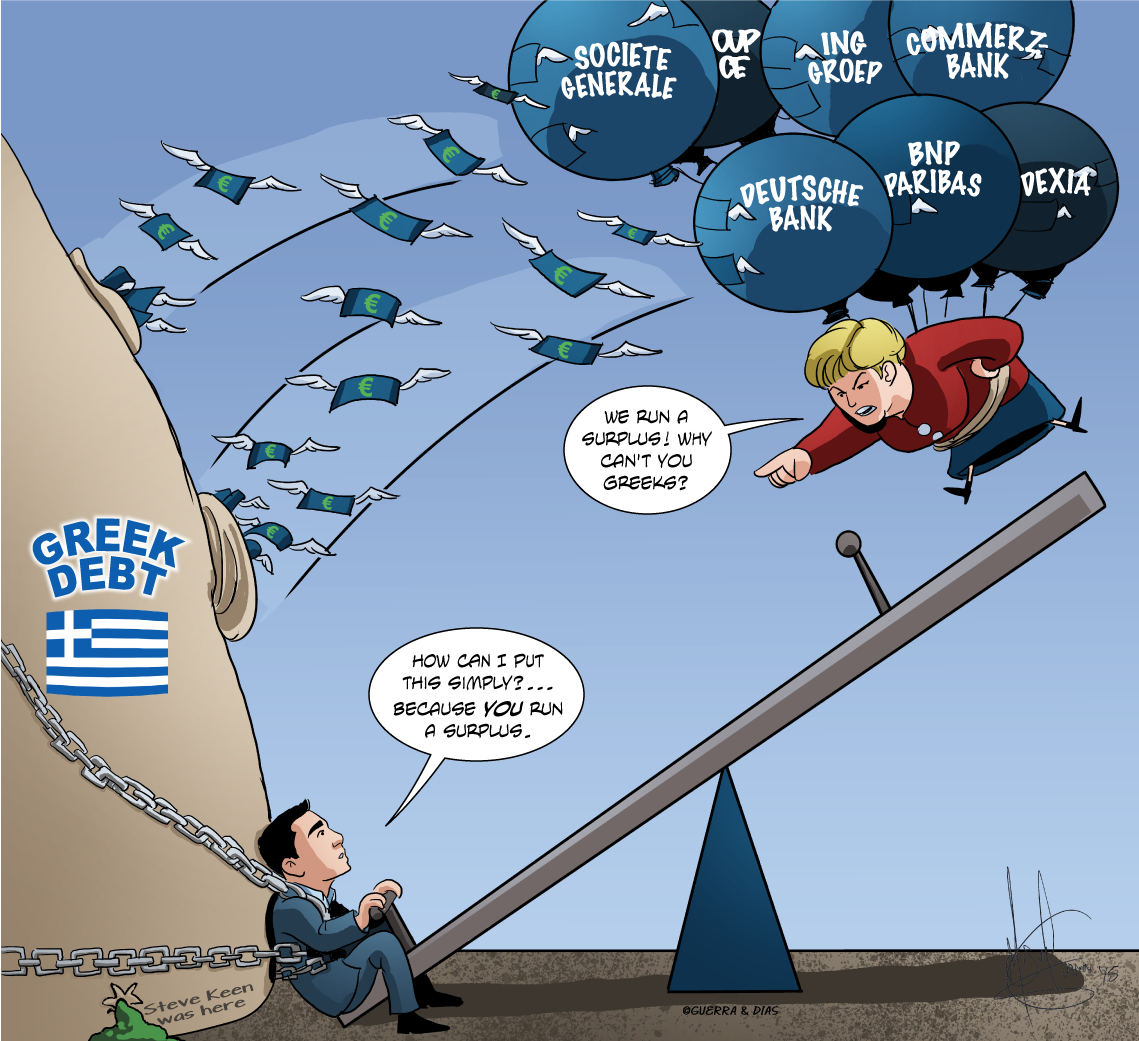

“In a museum the crystals are kept under glass cases; in zoological gardens the animals are fed. Having regard to the universality of reactions with environment, the distinction is not quite absolute. It cannot, however, be ignored. The crystals are not agencies requiring the destruction of elaborate societies derived from the environment; a living society is such an agency. The societies which it destroys are its food. This food is destroyed by dissolving it into somewhat simpler social elements. It has been robbed of something. Thus, all societies require interplay with their environment; and in the case of living societies this interplay takes the form of robbery. The living society may, or may not, be a higher type of organism than the food which it disintegrates. But whether or no it be for the general good, life is robbery. It is at this point that with life morals become acute. The robber requires justification.”And this all got me to thinking about Germany in particular. There is no country in Europe that has based its economy so heavily on engineering and technology—and few in the world (even a scandal of the magnitude of that consuming Volkswagen is unlikely to shake this). Certainly from a British perspective, where finance capitalism has been politically dominant for decades now, this is particularly striking. Likewise, there can be few countries in the world who are so manifestly proud—this is how it is projected abroad at least—of their economic productivity. This work ethic self-righteousness plays a large part in setting the political agenda for the whole of Europe, as was demonstrated so starkly during the the ‘negotiations’ with Greece this summer. The German Ordoliberal ideal of balanced budgets and fiscal austerity rests upon the material basis of a technologically sophisticated, export-based economy, something that is not easily replicated.

And yet the general consensus is that the German attitude towards technology is, and has perhaps always been, markedly sceptical (although see this for another view). Germans are understood to be among the most hostile in the world with regard to nuclear power, fracking, geoengineering and so on. The roots of this undoubtedly run deep—the whole early-to-mid-twentieth-century thing springs to mind (Heidegger!)—but the entire history of romanticism long before that, also.

I should add that I know very little about political economy and even less about German political discourse. My impressions are very much made from afar. However, the point I am trying to make is this: Germany seems to embody in a particularly pronounced form a contradiction broadly evident right across the Euro-American world (and perhaps beyond), a contradiction that the likes of the ecomods capitalise on. I have little sympathy with their politics—their strategy is consistent: demonise those to their left, build bridges to those to their right—but they are asking some of the necessary questions.

So, having said all of that, the last (but by no means least) panel of the EISA 2015 conference that I attended followed right on from this one and was chaired by Delf Rothe. ‘Critique in an Age of Complexity’: this is how my conference was concluded.

The four papers presented were: ‘Resisting Resilience?’ by Chris Zebrowski; ‘Warring in the Mind: Ideology, Truth and the Neuromarketing of Hope’ by Claes Richard Wrangel; ‘Assemblages and the Positives of the New Materialism’ by Jonathan Joseph and Robert Carter (only the former of whom was present); ‘Complexity and “critical government”: Kantian legacies, critical disjunctures’ by Regan Burles.

Chris, drawing on his recent book The Value of Resilience: Securing life in the twenty-first century, talked about hybridity as immanent critique and how resilience depreciates the non-adaptive. Claes, drawing on a broader research project on hope, discussed the neuroscientific conception of the mind as an adaptive system and how this, quite peculiarly, leads to new forms of politically questionable subjectivism. Jonathan levelled a scornful critique at ‘new materialism,’ particularly taking exception to the alleged levelling of human and non-human agencies in the ‘flat ontology’ of actor-network theory. He mentioned that the concept of assemblage might have some value as a tool for diagnosing neoliberalism but that was about the best that could be said of it from his critical realist point of view. Finally, Regan drew more from the Kantian legacy. To be honest, by this point my brain was fried and I can’t really remember what he said—but it was good!

On the new materialism point, Delf, as discussant, commented that perhaps Jonathan and Robert would be better off aiming their critique at one particular author rather than the group as a whole since this term ‘new materialism’ masks a lot of important differences (a point that I have made previously). From my point of view, Jonathan’s critique was nothing new and mostly relied upon only half thought through reductiones ad absurdum—however, having not read the full paper perhaps I should hold my tongue/fingers.

The question that stuck in my mind at the end of this session was the relative obscurity of ‘critique’ as a term that is constantly used within academic discourse but is used in a variety of different ways. From the strict Kantian sense of interrogating transcendental conditions of possibility to the more deconstructionist sense of ‘problematising’ and ‘destabilising,’ there are clear commonalities and shades and degrees in-between but critique remains, to my mind, a concept that is used almost invariably without any qualification and clarification and, perhaps it’s just me, but I am often left wondering what precisely it is supposed to mean—not that it is meaningless but that it is rather fetishised. I did raise this question in the final Q&A but was left none the wiser.

And so concludeth the conference.